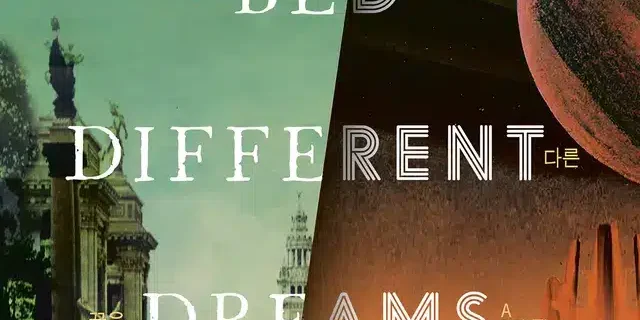

Ed Park – Same Bed Different Dreams (Random House, 2023)

Every morning, Ed Park sits at his typewriter for twenty to thirty minutes to write. He throws on a vinyl record of some sort. Usually, it’s classical music, like a Johannes Brahms piano trio or a Georg Philipp Telemann compilation. If it’s going well, he repeatedly hits “play” until he runs out of steam.

His desk is small, tucked away in a corner of the Upper West Side apartment that he shares with his wife, Sandra, and their two sons. There are no windows. In the closet to his left, the washer and dryer stand guard.

Park’s creative process is intentionally analog, purposefully hermetic. Outside of that curated authorial space, the world buzzes and distracts. So he avoids the temptation of Wi-Fi’s swirling void of pixels. He avoids the risk of lyrics, their pesky tendency to entangle an author’s literary thoughts as they travel to the page.

And though he could move his desk to another room, one with a view, he chooses not to. Like Soon Sheen, a character in Park’s latest novel Same Bed Different Dreams, he enters his own “Little Eden” and basks “in the unwiredness, free from all communication.”

“I think sometimes when you’re writing,” he explained, “you just really want to be in an enclosed space with not that much outside you.”

To an onlooker, such a creed of solitude comes to make perfect sense when she reads the literary mammoth that is Same Bed Different Dreams. It’s impossible to understand how else Park could have managed to unsnarl and decode the obscurest fragments of history, memory, and emotion whirling around within him, much less within everyone else.

The “wild, sweeping novel”—as its publisher, Random House, anoints it—almost evades summary. Its timeline jumps from dates between 2016 CE and thousands of years in the past, its setting from Korea to Russia to Switzerland to the United States, and its cultural referents from Marilyn Monroe to Tim Horton and Kim Il Sung.

And at first glance, Same Bed Different Dreams’ division into three alternating and recurring sections—“2333,” “The Sins,” and “Dreams”—appears mind-boggling. However, with patient attention and an appreciation of Park’s crisp prose, a reader can see patterns emerge. The “2333” chapters follow Parker Jotter, a war veteran and science-fiction author. “The Sins” centers on Soon Sheen, an employee at an omniscient technology company. The “Dreams” present themselves as parts of a mysterious, unfinished manuscript. Park’s throughline is the Korean Provisional Government (KPG), a pro-independence organization formed in 1919 in opposition to Japan’s occupation of Korea that began in 1910. He imagines that it still exists, far beyond its supposed dissolution in 1945.

By Alisyn Amant

Read More >