Empowering Others Through Compassion, Relationships, and Racial Reconciliation: Steve Park

Welcome to the Korean American Perspectives podcast. My name is Abraham Kim and I’m the host of this podcast and today we have a very special episode for you.

Abraham Kim

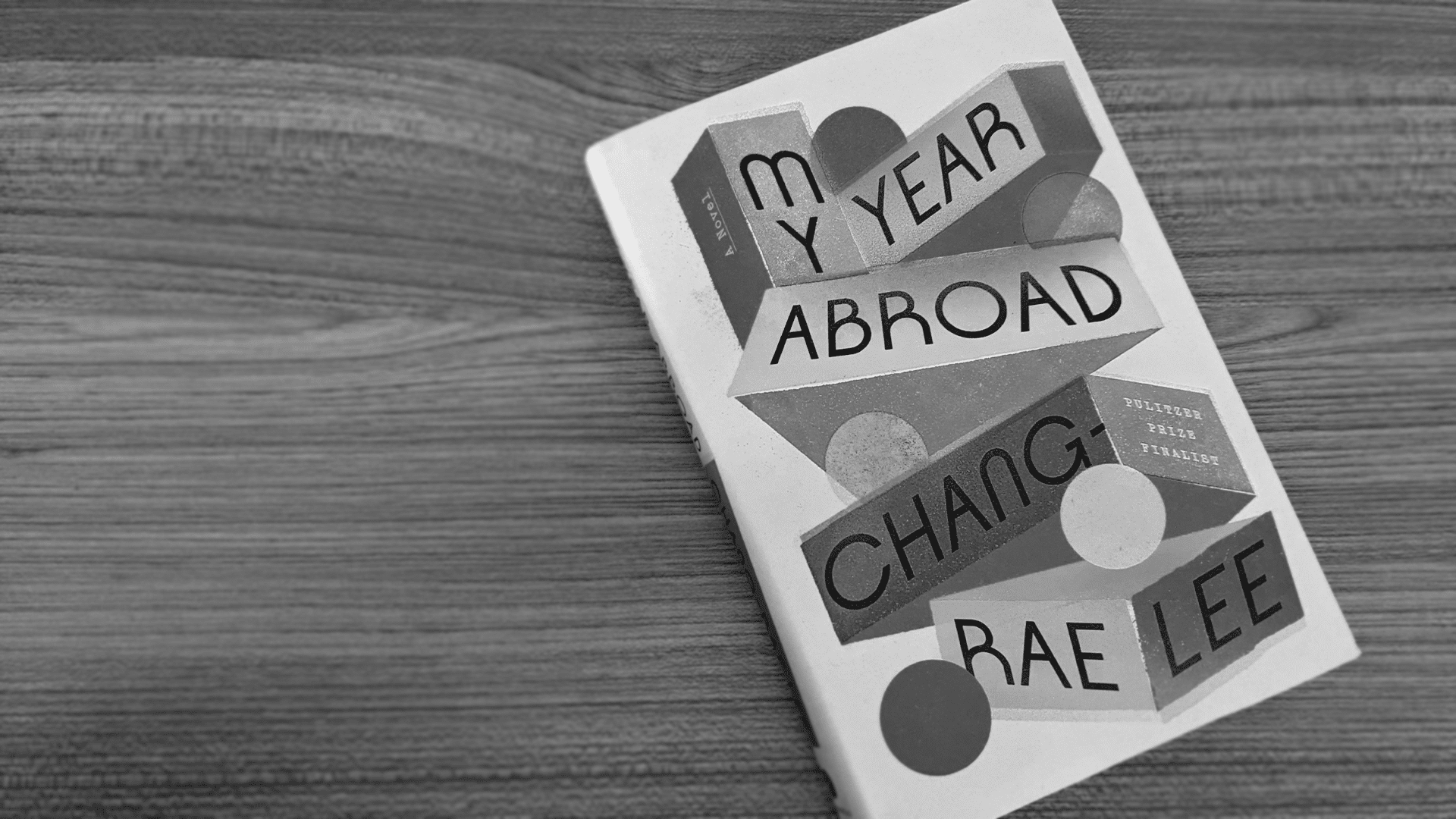

To kick off CKA’s arts, culture, entertainment, and sports (ACES) initiative, we have Chang-Rae Lee who is a celebrated Korean-American novelist and who just released his newest novel My Year Abroad. To speak with him, I will actually be handing the mic over to Dr. Stephanie Han, a member of CKA and also an author, educator, and speaker.

Abraham Kim

In this episode, Chang-Rae Lee and Stephanie Han take a deep dive into My Year Abroad and explore the psyche of the book’s colorful characters, their wild journeys, and the Asian American experience. They also connect these discussions with Chang-Rae’s personal life as a Korean American immigrant, his identity formation, his colorful career, and even how food plays an important role in his writing.

Abraham Kim

So sit back, relax and enjoy this conversation with Chang-Rae Lee and Stephanie Han.

Dr. Stephanie Han

So welcome Chang-Rae Lee. I’m very excited that you’re able to share your insights about My Year Abroad, which is a fantastic read – I loved it, and your writing journey with the Korean American community.

Dr. Stephanie Han

My first question has to do with this idea – you dedicated this book to the teachers in your life, obviously, and I felt like this was a theme you actually have explored a lot in a lot of your books, how we learn from each other and who teaches us what and how we make sense of our life and our circumstance.

Dr. Stephanie Han

And so what I’m curious about is what led you to explore this dynamic further with this particular ethnic, racial, and social makeup of this pair of Pong, this much older Chinese

immigrant, and then we have this, you know, 12-percenter, young Tiller who reads probably as white, but claims some Korean blood.

Dr. Stephanie Han

I was wondering if you could maybe speak to this and how this might have influenced this teaching student thing.

Chang-Rae Lee

There’s always multi-layered and complicated dynamics between characters, but I knew that a primary one between these two would be one of mentorship. It comes from something that I always think about especially when I finish a book and to tell you the truth I don’t finish many. I always think back to all the people who had helped me get to the place where I am in terms of my work and the ways in which I think about my work, the ways in which I think of myself as a teacher, all those things.

Chang-Rae Lee

I know that goes back to the very beginning when we first came to the country and my mother and father, although very educated and very interested in my education, didn’t really have a sense of how I should be educated and so I depended so much upon my teachers and also very much so on the librarians in our community. I remember my mother dropping me off at the library every day for three or four hours and basically allowing them to guide me in my journey, intellectual and cultural life.

Chang-Rae Lee

I bring that up because it’s part of my life, but also because it’s part of what this book is about. It’s about being introduced to a way in the world, not just to places and not just to other people, but a way to think about oneself, a way to think about oneself in a context. Then also, of course, how to begin making oneself, constructing a self. Especially constructing yourself when the culture around you isn’t one that necessarily recognizes you for all that your legacy is, all your traditions, all the things that you come from.

Chang-Rae Lee

So it was absolutely something that I thought would be central to the novel given the trajectory and the kinds of stories that I was going to pursue in this novel, which is a story about adventure, I suppose, but really all adventures are adventures are about the travel of a consciousness and a psyche through his or her life. That’s really what all novels are about.

Dr. Stephanie Han

I’m very curious, however, about the choice to make in terms of the background of these characters, who and what they are. I mean, I guess I’m looking a bit at China as a global force and the narrative of this older Chinese man, and then the reality of what immigration might result in, which is the sort of physical dissipation of visible Asian identity, right?

Dr. Stephanie Han

And so I didn’t know if you could speak to this. I mean, you know, we’re looking at Asia, but then through the eyes of somebody who has been removed from it, and yet there’s this tension and I didn’t know, in terms of learning and knowledge, what you might think about this.

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, the choice to make the narrator of the novel this young fellow Tiller, one-eighth Asian, was absolutely deliberate. As you suggest, he’s someone who has always passed in his life in the mainstream, not to be anything special. In fact, the opposite. To be unnoticed so that he could just go along and not have to think much about his ethnic or racial legacies.

Chang-Rae Lee

I did want him to be someone, particularly a younger person who was just at the cusp of beginning to ask lots of questions about who’s in his background. In his case, his mother. I wanted to open him up to beginning to think about and to be engaged with the idea that part of him, part of the streams, and we all have different streams going through us genetically and culturally… But that part of those streams for him do take him towards Asia.

Chang-Rae Lee

So it’s no accident in the novel that he finds this particular newcomer immigrant, Chinese fellow who is not really Chinese American. He’s been described that way, but I don’t really consider him Chinese American. I consider him a global diasporic figure who has his own identity in a way, but of course is astride Asia and feels most comfortable there.

Chang-Rae Lee

This, I think, is what Tiller has been looking for in his life. I think he’s found that there’s been an emptiness and void in his life that is a little mystifying to him and he can’t quite put a finger on it. I think hooking up with this fellow Pong, he begins to solidify certain notions about who he might be, how he should model himself from philosophical ideas.

Chang-Rae Lee

There’s a scene in the book where they’re in a Korean shower thing where they’re kneeling and he has fun with it, but he also kind of thinks of it seriously as, ‘huh, is this a tradition that I should follow even though it’s just a modest human one?’ So those are the kinds of things that I wanted him to think about as he begins his journey into this wider world.

Dr. Stephanie Hsn

Yeah, I was curious, there’s this great quotation… I’m going to skip a little head in the karaoke scene where they’re all singing. Then, Tiller says he noticed this brother-sisterhood vibe in the room and elsewhere, he’s experiencing this kind of idea of being subsumed by this Asian consciousness yet he does not read as Asian. So what is the conflict of this? What is it that he’s tapping into potentially?

Dr. Stephanie Han

And I also thought it was curious and totally fascinating that this wasn’t a Chinese idea or particularly a Korean idea of an Asian group. This was a Pan-Asian group. All the men in there… They’re from Sri Lanka, they were Chinese, all these different groups and people

that evening, and I was thinking, this is an Asian American kind of conception of a group. So I didn’t know if you could speak to that idea of how we find our group? What is that group and what is that feeling? Is that a different feeling?

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, just talking outside the novel, I think we find our groups in the ways that we find out anything about life. Our experiences are particular to us. My Korean American experience, as I always say, is very particular to me and to my family say my sister and my small group of friends. My Korean American experience for example was vastly profoundly different from those of my cousins who lived as the crow flies maybe 15 miles away, but in an ethnic enclave surrounded by other Asian people with a different primacy of certain languages, different kinds of cultures at school. Whereas I grew up in a place that was an Italian American and Irish American Catholic neighborhood where we were one of three families who are non-white.

Chang-Rae Lee

We started out at the same place, but the context is so powerful and that’s what I always want for people, particularly my students when they ask me. I said, ‘you can ask me about my experience, but interrogate and investigate your own in all the micro ways and that’s where you’ll find the ways in which you’ve been formed and that you’re forming things back, right?

Chang-Rae Lee

It’s not just this passive experience. We respond to it and so in the book, because Tiller is one-eighth Asian and curious about that, I didn’t want him to focus on one particular nationality, one particular line. I like the idea that he just appeared and this probably comes directly from my moving out to the West coast fivers years ago. Again, I grew up in a fairly mainstream white community and a larger culture that was intellectually and culturally so. Moving out to San Francisco and spending as much time as I could in Hawaii, I feel like I’m in just much more of an Asian inflected realm and around that.

Chang-Rae Lee

It’s not perfect by any means, but that does have different kinds of engagements, different kinds of pressures, different kinds of welcoming all those things. Certainly for me, something that felt like a different kind of comfort level than what I had grown up with for 50 years of my life. So in some ways, this reflects what happens to the book. It’s a coming of age book and also kind of a mid-life crisis book. I guess it’s a book that aligns with who I am at this moment as well, which is maybe I’m growing into something new to out here that I didn’t have before, which I like.

Dr. Stephanie Han

So I wanted to ask, I feel that, especially from your last dystopian novel and this one, there’s a definite shift. I’m thinking this, as you said, this might have to do with your move to the West coast, but there’s a definite different feeling. I feel like I’m witnessing a pivot of your lens to Asia and to this kind of a global question of how we intersect. So I’m curious about your research trips, your process, you know, karaoke here in Shenzhen or a foot massage, the electronics in the mall.

Dr. Stephanie Han

This is [written by] somebody who has taken these kinds of [journeys]. From the way you write, I know that you took those journeys and I’m curious, did you start out writing and then you journeyed or did you journey and then get inspired? Because your lens has definitely shifted.

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, On Such a Full Sea has an Asian element to it for sure. In fact, I would say it’s my most Asian American novel. It’s about an Asian American community and in some ways that community is kind of Hawaii. But it’s my second novel that’s focused on China. I was originally going to do a novel about Chinese factory workers. I ended up writing this dystopian novel that included some production factory workers in a speculative context, but I guess I wasn’t finished with it.

Chang-Rae Lee

I had a friend back in Princeton, who is the model for the Chinese businessman Pong Lou, and I really enjoyed him and enjoyed hearing his stories – a wonderful fellow. But again, I was wrapped by the way in which he saw himself in the world, which is not anything like what my growing up [was], how we kind of felt as immigrants.

Chang-Rae Lee

Again, we’re not in an immigrant enclave. We did feel as if we were alienated a little bit, not because people were mean to us, just because we didn’t know the language very well. We didn’t know the customs very well. We didn’t have a safety net financially. So we were a little bit, quite frankly, cowed, very careful. Very wary of outsiders, wary of doing the wrong thing. But this fellow who Pong Lou is based on had an absolutely different sense of himself in the world, a sense of possibility. That sense of possibility and ambition was something that I felt like, ‘oh, maybe I had lost that sense of ambition and possibility’ [from] being settled and comfortable in my life.

Chang-Rae Lee

Seeing that as, and of course we’ve been hearing so much about the Asian tigers and the rise of Asian power, particularly led by China, which of course is inexorable and inevitable. We all see where it’s going, right? This will be a Chinese world and also an Asian world too. We’re not even talking about India yet. It is, I think, a recognition on my part of what I’ve been feeling, which is probably the last American century and that we as Americans, and I consider myself American and patriotic in all ways, but I think we have to recognize how the world is changing. How the positions are changing and the ways in which maybe American exceptionalism also has to change our ideas about that.

Chang-Rae Lee

I find that just very interesting and I, of course, as a novelist, those implications have ultimately for me and for you I’m sure, end up being singular and personal as expressed in individual people and characters.

Dr. Stephanie Han

So did you feel that Korea then as a nation and its issues – did that figure a lot into your development growing up? So, you’re talking about China, obviously we’re the Council of Korean Americans, so I’m gonna ask you a little bit about Korea and I’m just curious, I know that you wrote that your dad was from Pyongyang, North Korea so that tie would have been cut, but did you grow up visiting Korea? Did you go to language school? How Korean were you in other words? And what does that actually mean?

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, that’s a good question. We arrived in America in 1968. Our first trip back to Korea was in 1980, so quite a few years and in the first few years, would it have been because we didn’t have enough money. My father is a physician , a psychiatrist. At some point, he was able to make a decent living, but I think maybe because my father was from the North and partly that’s why I think he and some of his classmates from medical school in Korea decided to make a new life here. I think they felt that maybe there was a glass ceiling for people from the North as I think a lot of people in Korea feel from different corners of the country.

Chang-Rae Lee

So we grew up without really any relatives. We would have relatives visit every once in a while, but we were essentially alone for much of our lives until after 1980. Some relatives came over, but we didn’t even see them that much then when they lived in different parts of the country, some in Canada. So I think, sure, my parents went to a Korean Church in Queens, New York. It was an hour drive, but they weren’t really religious people. They were just interested in communing with other Koreans and hanging out with other Koreans and hanging out afterwards for tea and duck, as I did, you know?

Chang-Rae Lee

So it was a life that inside the house was intensely Korean, but of course, it was the Korea of 1968 that my parents brought over. It never really changed, for better or worse, because they were also cut off from all things Korean. I think that would be very difficult today given all the Korean media, technology, Skype, Zoom, everything like that. So I don’t know that there were very many phone calls. When I saw my grandparents for the first time, although I was born in Korea, I was a child, a baby… It was amazing to think that was the first time I really saw them. Did I really get to know them? No, I really didn’t. So I would say that we had quite a Korean upbringing and a Korean sense of ourselves, but we felt a little bit marooned, I suppose. Part of that was intentional for whatever reason for my parents.

Dr. Stephanie Han

A lot of young Korean-Americans, this is when they rush headlong into identity formation, joining Asian American groups, and trying to figure out who they were, do the homeland tour, do all that. Was that something you felt propelled to do or not? I didn’t know if you could speak to that.

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, I again went to boarding school. I went to Exeter, which now I think is 25% Asian or something, some huge number like that. You went to Andover, I know it’s probably similar. Of course, we went to school at a very different time when there were just a handful of Asians, and a handful of Koreans. Although there were friendships there, it wasn’t for me, at least in my experience I did not gravitate towards Korea groups just because it wasn’t my life and my interest at the time. Not that I didn’t have Korean friends, but I suppose I wasn’t in the Korean club and just there. And that was fine at the time. It seemed suitable to me.

Chang-Rae Lee

But I think as I got a little older, particularly in college and then after college, I started to see more and hang out more with my Korean friends from my youth and new friends that we’ve met. I think it’s been kind of a gradual uptick of all that kind of activity. Not just being with, but actually thinking about it and talking about it and being conscious of it. I think that’s one of the things that, not growing up in an ethnic enclave like Queens or LA Korea-town or something like that, I always was very conscious of it, right?

Chang-Rae Lee

I mean, if you grew up in a community where you totally belong and everyone looks like you, you don’t think about it. It’s just life, right? But I think about it all the time, because it’s not “natural” for me in the way that I grew up and that’s probably also what contributed to my interest when I started writing. To think about those issues because identity is a really complicated thing. If it can make you feel good to say, ‘no, this is who I am. These are my legacies.’ But at some point, that’s just a contrivance too, right? Because we choose who we are. We can’t choose our blood. But we choose who we are in every aspect of our lives. So that’s what I guess I ended up doing.

Chang-Rae Lee

When students talk to me about that and I teach a class at Stanford called Asian American Autobiography where the students are just writing about their families, their backgrounds, all the things about their sexuality, schooling, their parents mostly, and I think they come into the class thinking, ‘okay, this is going to help me figure out who I am.’ But what ends up happening in the class is they end up realizing there’s a whole new host of questions that they have to start asking themselves.

Chang-Rae Lee

Because once you dig into it, once you actually get into those details that have all these little adjacent details and corollaries… It’s endlessly complicated and again, I think that’s a good thing. It’s endlessly complicated, but it becomes more and more distinctive to that person. Not that we don’t have commonality. We absolutely do. I have very close Korean buddies here, we have so much in common. We love hanging out together, but of course our experiences to this point where we’re having a beer at the golf club are totally different and our world views may be even totally different. But we’ve come to a place where we do have a sense of brotherhood, sisterhood, community. But again, that sense of brother and community and sisterhood is probably different between us, right? Different things that we’re appreciating, focusing on, and that’s cool. That’s great.

Dr. Stephanie Han

This is great and this is another question that kind of touches on this is your interest in food, which is long abiding. It appears in all of your writing with great gusto. It’s really fun to read your food writing and I was thinking about food and how it manifested in terms of the relationship. There aren’t any good meals between Tiller and Clark, his dad, not any memorable good ones. I think that’s just something about the relationship, but yet there are these food adventures with Pong and then of course, with, Val and VeeJ, it’s about food. So I was wondering if you could speak to something about food and what does food do? How do you see food in your life? What is the role of food for you?

Chang-Rae Lee

I mean, let’s face it. I, and I don’t know if it’s because we’re all Korean or Asian or something, but we know what the role of food really is. It should taste great and we should love it and that we can talk about it endlessly about different ingredients, different methods, but ultimately it’s about connection and it’s about memory and it’s about blood and guts. That’s why it doesn’t have to be the most fancy food or the most “tasteful” food.

Chang-Rae Lee

Someone asked me the other day, what was my madeleine moment. One of the dishes that my mother would make me when I was a little boy would be just like, kind of a watery rice, warmed up… Not juk, but just kind of rice with hot water on it, basically. Then she would cut up little pieces of deli ham or bologna and I would put that in a spoon and have that. And boy, doesn’t that sound kind of awful. No gangjang, nothing. No chang-gi-reum, nothing. But I must say, I always think about that.

Chang-Rae Lee

I don’t think I’ve had it since I was eight years old, but I always think about it. So why do I think about it? Because I think about the way that our kitchen was, how she had things arranged. I can see her preparing that, I can see also more deeply into it – some of her happiness and frustrations. I can remember my sister sitting there not wanting the same thing. I can remember that whole apartment and that whole time. That’s not just because I’m a novelist and think about these things. That’s what we all do, you know?

Chang-Rae Lee

Maybe I am more explicit thinking about those things and seeing them than maybe other people are. Maybe I am more practiced at that, but that’s what food really is. Food is an opportunity for a moment of real connection and engagement with the world. Sometimes it’s not fun. It’s not a happy one. I can remember certain things that ping me in a difficult way with certain meals. That for me is why and because it’s something that we do everyday and some of us do more than three times a day. I know my daughters too, that’s who they arrange and organize not just their day, but in some ways their memories, in some ways our lives.

Chang-Rae Lee

Of course, it’s no accident that we grew up in a Korean family and that’s where a lot of this stuff happened. Some of that’s cultural as we know. Some Korean families, as our was, are not super talkative, but we did talk at the table. Other kinds of families might do it over gin and tonic on the porch. We didn’t do that. My parents didn’t drink. I do that now with my daughters, but we did that over in that basement of that church just having some kind of stale duck and not so great tea. But boy, I can smell that whole place and I can see all the people. So it really is the stuff of life for me.

Dr. Stephanie Han

I’m also interested, you’re exploring here through the drink, the special drink. I don’t want to create spoilers for everybody, but there’s a trade and a business that’s going on and there’s a sort of an elixir or a health drink and there’s an exploration here of the wellness industry. And I always thought that actually the contemporary wellness industry is like a mild watered down Asia import, you know, it’s everything that we associate with wellness from green tea to like yoga stretching, to be thankful, and it’s not a monotheistic idea. These are all Asian philosophies, exercises, practices, products, and I was just wondering a bit about some of the paradoxes or the myths that you were trying to get to with drums and the yogis.

Dr. Stephanie Han

I mean, it was pretty funny. I mean, this book is really, really funny. This is the funniest book that you’ve written and it’s sort of a take no prisoners [book], you don’t spare anybody. So I was wondering if you would talk a little bit about that.

Chang-Rae Lee

Yeah, I do yoga not in a serious way, but just to stretch out my bad back. Like everybody else, I want to be well. But of course, I do poke fun at the idea of wellness and a character in the book says, ‘you Americans, you’re always worrying about wellness. There are bigger problems to think about here. It’s not just your blood pressure, right? It’s everything else.’ And so that’s something that I wanted to poke fun at.

Chang-Rae Lee

The long-standing cultural appropriation that’s gone on with the exotification of the East and it’s “ancient wisdom” and have fun with that, but also say something about the kind of, unfortunately, chronic condition of illness in our world and the way in which our civilization is always ill from the world climate, to our politics, to our gender dynamics, to everything. That there’s something off that we’re constantly trying to put a new bandaid on. Trying to look for that magic thing, that elixir, that a mortality drug, which is discussed in the book a little bit. Of

course, it’s just a mask and a veil for what the real problem is, which is something much more systemic.

Chang-Rae Lee

So in some ways it’s a critique of our Westernized civilization, our Westernized world, frankly. I think we all see, we all know all those things. I don’t have to go through them, but of course just wanted to have some fun with it in the book.

Dr. Stephanie Han

You talked a little bit about your journey – you went to Exeter and I read an essay about your mother’s little bit of anxiety about you going off, you’re moving farther away and you became something maybe that she wouldn’t have been able to conceive of, right? You went on to Yale and then apparently you worked for a year on Wall Street. I also read you worked at the Capitol. So I was going to ask you about that – what office you worked for at the Capitol, that’s a little bit more recent. You said you did a bunch of part-time jobs while you were writing your novel. And I thought a lot about Tiller’s because I thought, ‘I bet he was a dishwasher at one

point’ just based on your description of Tiller.

Dr. Stephanie Han

I think that there’s a lot of focus now on young people doing the right internship, doing the right thing, a lot of pre professionalization at a young age, a lot of fears and anxieties that parents have that could be well-founded fears, but inhibit a kind of exploration. So I just wanted to have you talk a little bit about what are all the things that you did before you became Chang-Rae Lee, the novelist we know.

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, I was a dishwasher, it was a summer job, a classic high school, summer job. It was the

most disgusting job I ever had, and if people read the book, they’ll see that I had some fun with it too. I thought that job was actually pretty valuable to me ’cause you meet all sorts of people from every walk of life. Especially for someone whose work now depends on understanding things about people and observing as many people as possible, which I, frankly, think probably a lot of industries would lead to some expertise in some, a lot of industries. It was a job that, as I said, I think in the book, at the end you survive. At the end, you learn something about yourself and you learn something about just sticking your head in there and just keep pushing.

Chang-Rae Lee

When I was trying to write my book after I quit my wall street job, which wasn’t a bad job at all, but I did it for all the reasons that, well the kind of thing you’re talking about, trying to get our kids in the most elite, remunerative and successful kind of lines. We all understand why, right? It’s a tough world out there and that’s totally honorable, but I painted apartments. I wrote for a free press. I did little food reviews and restaurant articles.

Chang-Rae Lee

I was, this was my favorite job, the Assistant to the Dean at the Fashion Institute of Technology. I did that for four hours a day and saw all these crazy people, designers and again, it was stuff that at the time I just needed money and I did whatever I could. Oh boy, do I remember every detail of those jobs.

Chang-Rae Lee

I like what you say about the pre-professionalization of everything, the importance of the right internship and I always think you’re going to be doing this job for the rest of your life. Just go out and whatever you’re gonna do, do a great job at it. See the whole thing, really throw yourself into it. I’m sure it won’t be anything, but valuable and of course, it’s mostly the parents who are the sources of pressure and worry and the kids just take that up. If we weren’t so worried about it and said, ‘hey, go out and make a living. Go out and don’t depend on any allowance and then see what you can come up with.’ I bet they’d come up with something

pretty darn interesting.

Dr. Stephanie Han

So do you think Tiller is kind of an ideal? I mean, Tiller is Tiller’s doing all this stuff

that you’re talking about, right?

Chang-Rae Lee

I wouldn’t say he’s ideal. I think maybe he’s a little reckless. I think he courts danger

a little too much. So I wouldn’t want that for my own daughters, but I do think that not worrying so much about it, especially if you’re from a family that has some means, and I’m not talking about being super rich, I’m just talking about one that can take care of itself.

Chang-Rae Lee

This is the last opportunity to actually engage with what’s really going on in the world and

how most of the world spends its day. That’s part of what the book is about. It’s fantastical at times, it’s intensified at times, but the whole book is about trying to get this young fellow out in the world so he can see all the aspects of it and how those little facets reflect back on him and

how he takes those in. Does he learn from every single one? I don’t know, but he’s learning something I hope and I suppose that I subscribed to that idea for just one of our kids doing whatever.

Chang-Rae Lee

My daughter worked at a luggage store last year before the pandemic and she didn’t really want the job and she turned out to be pretty good at selling luggage. You know, they

gave her a big prize and it shocked her, in fact. I’m sure that’s going to be valuable for

her in whatever she ends up doing.

Dr. Stephanie Han

So, these are some of the questions that came up and then I might revert to another one, but the question was about your own idea of Korean heritage as you’re passing it down, how Korean are your kids and how do you feel about that? Do they claim the Korean identity?

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, my wife is not Korean. She is Anglo-European American and so [my kids are] half. I would say that they, as they’ve gotten older though, they definitely have been identifying

more and more with Korean culture, Korean food, Korean media. My younger daughter’s totally into BTS late in her life. She’s 20 and having a lot of fun with that. So that really has nothing to do with me and us. I didn’t send them to Korean school.

Chang-Rae Lee

I do hope that my younger daughter, who’s still in college… She’s planning on spending a semester in Korea and studying there. So I’m happy about that. But I’ve never pushed them very much. I think I just let it kind of happen and I see that it is happening. I didn’t want to try to curate that experience for them too much. When things are done like that, I just don’t

think you’d pay attention as much and I think once they get an interest in something, and particularly my older daughter is really into cooking Korean foods and she also wants to spend time in Korea now. She talks about that even though she’s in the working world. So where that came about and how that has come about, I can’t really trace, but it’s happened.

Dr. Stephanie Han

And there was a question about seeing a different side of your personality, which I also thought with this book, it’s humorous, it’s funny. I mean, I read that many people think

that it’s over the top, but I think you really captured a certain energy and vitality of what it means to encounter these things for the first time. It seems very accurate, not over the top at all.

Dr. Stephanie Han

And then I was curious, one of the questions is about your personality and a different side of you and what is it that prompted you? All of a sudden, it’s this young narrator doing these ‘pretty out there’ things. We’re taken into this different space and you can see the trajectory from On Such a Full Sea to now, but I mean, why did you go this route? Is it going to be

more and more this way? I’m wondering actually too how this is connected to your being here in the West and like, are you more comfortable?

Chang-Rae Lee

My previous novels have dealt with some pretty heavy things – Korean war, sexual slavery, with the jeongshindae, the really serious,vpretty intense reckonings of identity. And so those books, they have some moments of lightness, but they’re pretty serious books. Just because of the subject matter and what I was thinking about, there’s a certain modality that goes with those books and those modalities didn’t necessarily include my daily private human life and personality. Not that they couldn’t have gone in there, I just had no interest.

Chang-Rae Lee

And so this particular novel, because of what it’s about and because it’s a younger fellow, I was also feeling maybe this kind of newness, sense of newness and a sense of renewed possibility, perhaps moving out to the West coast, new job, kind of starting over, which

was absolutely intentional.

Chang-Rae Lee

I was very happy at Princeton professionally. So in some ways it’s a new adolescence for me, but maybe a cultural adolescence, ethnic adolescence. So I think I invited in, particularly

because of the character, more of who I am just day to day, the kind of play of my thoughts, the range of them, the kinds of language high and low, that’s me. I don’t know if that will continue. I think it just depends on the book. I think it really does depend on the book.

Chang-Rae Lee

I will say that I enjoyed it. I enjoyed this different kind of exertion if that’s the word for it. Different kind of stance, I guess, and aesthetically, so I’m glad to have found it

and to have been able to explore it in my work.

Dr. Stephanie Han

You’ve been really chronicling a lot of this sort of detailing Asian-American male masculinities. What does it mean to be an Asian-American man? What is manhood? How does one define masculinity? And I was curious, I thought Tiller is actually quite a feminist, a young feminist asking questions about his role and, you know, curious in that way. So I didn’t know if you could speak [to this]. Do you feel that your portrayals are the same or have they shifted? Do you see Asian-American masculinity as shifting now – Korean American masculinity? How do you think about that when you’re writing, if at all?

Chang-Rae Lee

Well, in this particular book, I think he’s very conscious of how the women in his life and in his encounters, how they’re feeling and thinking, and if that makes him a feminist, fantastic. If that makes him a humanist, fantastic. Maybe that’s as much of it. I think so much of what goes awry is that we can’t imagine the other, we can’t imagine a different worldview or different sense of self in a context and are so locked into our private or egoistical position.

Chang-Rae Lee

I don’t have a big agenda or thing about male masculinity, particularly Asian male masculinity, but I must say that I’m so happy to see so many more, particularly in the mass media, in Hollywood and TV, more portrayals of Asian males and Asian females that are different, nuanced, interesting, that they allow people to be people rather than types. And I think that’s so important for all of us, especially the younger people who are as younger people do and maybe even older people, we have this negotiation all the time.

Chang-Rae Lee

We’re modeling ourselves. Like, is that who I am? Is this who I am? Is that how I should be? If we don’t admit it, those little frictions are always there, so to see more of them where they’re varied and positive and again, distinctive rather than somehow standardized, normative, stereotype or racist, I think is great.

Dr. Stephanie Han

This was so great to hear from you. I could ask so many more questions in detail about the book. I just think it had a lot of energy. It was really fun. I think it was spot on in terms of

a global picture of what’s unfolding now, and also kind of an invitation for young people to explore, to take risks of the heart per se and so I really appreciated that.

Listen and subscribe to our podcast from your mobile device:

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | RSS Feed | YouTube

Introduction

In this episode, Chang-Rae Lee and Dr. Stephanie Han take a deep dive into his latest novel, My Year Abroad. They explore the novel’s themes, its colorful characters and adventures, as well as how food plays a role in Chang-Rae’s writing. They also connect the novel with the Asian American experience and discuss how identity formation is very particular to each person as well as the myriad of complexities and questions it presents.

Chang-Rae Lee reminds us that it’s important to take risks, journey throughout the world, and ask questions especially when discovering oneself.

Additional Links

Special Thanks

Stephanie Han, Ph.D., Guest Host

Reham Tejada, CKA in-house podcast producer

Gimga Design Group, graphic design and animation